The world of work is changing, fast, deep, and wide, and our way of thinking better catch up.

Pain is inevitable, suffering is optional. (Haruki Murakami)

The nice part about being a pessimist is that you are constantly being either proven right or pleasantly surprised. (George Will)

Everything is urgent except payment. (ancient freelance proverb)

I believe the general mood of the debate on the future of work is too optimistic and that European societies will not escape what Keynes called technological unemployment, meaning we won't be able to invent new good jobs faster than the emerging technology is destroying the old ones.

The employment opportunities of the future will be profoundly constrained by the capacity to automate work, and by the abundance of labor. Those two forces will combine to generate an employment trilemma: new forms of work are likely to satisfy at most two of the following three conditions: 1) high productivity and wages, 2) resistance to automation, and 3) the potential to employ massive amounts of labor.

Due to the reduction of the amount of good and well-paid jobs, we are very likely to face job-based polarization : widening inequalities between those who have access to good-quality and skills-intensive work and those who end up being low-paid employees in inferior jobs.

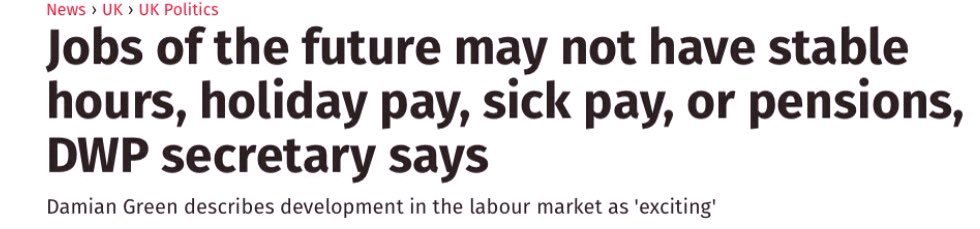

An article in The Guardian speaks of the "terrifying reality" of the impact of automation :

The debate on the impact of the 4th Industrial Revolution seems to be focused on numbers - jobs lost vs. jobs gained - and too little on job quality, on the social and legal environment of these jobs, their predictability and associated benefits. This is how we got the gig economy, the precariat, and in-work poverty.

The atomization of jobs into a myriad of routine tasks with quantifiable outputs, very likely only minimally coordinated, brings to mind Henry Ford's disturbing statement that it doesn't take a full human to perform a wide array of operations in his car plant. To me, the gig economy in its non-hobby manifestation is underpinned, to a considerable extent, by a line of thought that dehumanizes labor and the laborer. People who, in the absence of a backup / safety net, are forced to accept a pattern of fragmented, on-demand, low-paying activities, are relegated to a life of perpetual uncertainty, with serious psychological, interpersonal, and financial costs (see e.g. the report on experiences of individuals in the gig economy).

In many places, the disruption of the job market will make the issue of dependable and secure housing - if not questions of basic subsistence - even more urgent. Without policy intervention, the technological revolution is set to exacerbate regional inequalities.The same bleak vision of the future is shared, among others, by a report of the European Commission SFRI Expert Group, which speaks about "job-scarce economic growth" and "a transition period [with] both more unemployment and insufficient talent" (p. 15), and warns that "the developed world might become a low labor-cost economy were workers want to compete against automation" (p. 16).

* * *

The debate on the impact of the 4th Industrial Revolution seems to be focused on numbers - jobs lost vs. jobs gained - and too little on job quality, on the social and legal environment of these jobs, their predictability and associated benefits. This is how we got the gig economy, the precariat, and in-work poverty.

The atomization of jobs into a myriad of routine tasks with quantifiable outputs, very likely only minimally coordinated, brings to mind Henry Ford's disturbing statement that it doesn't take a full human to perform a wide array of operations in his car plant. To me, the gig economy in its non-hobby manifestation is underpinned, to a considerable extent, by a line of thought that dehumanizes labor and the laborer. People who, in the absence of a backup / safety net, are forced to accept a pattern of fragmented, on-demand, low-paying activities, are relegated to a life of perpetual uncertainty, with serious psychological, interpersonal, and financial costs (see e.g. the report on experiences of individuals in the gig economy).

* * *

Maybe is time to rethink the central role of work, a major source of meaning and sense for one's life - the reverse being that its absence leaves a void not easily filled. The 2015 British Social Attitudes survey found that "jobs are valued beyond their financial benefits : almost two thirds of respondents say they would enjoy having a job even if they didn’t need the money, up from half in 2005". Apparently, even a Universal Basic Income wouldn't drastically reduce people’s demand for jobs, at least for older generations. This is entirely understandable, considering the fact that employment provides us not only with an income but also five 'latent' categories of experience (identified by the social psychologist Marie Jahoda through ethnographic research) : time structure, externally generated activity, social contact, collective purpose, and status and identity.

It seems to me that is urgently needed a new cultural consensus, one that provides an answer to the thorny question "When technology can do nearly anything, what should I do, and why?" It would have to accommodate the fact that work will be a choice not a necessity, and that a considerable share of the population will live on some sort of means-independent social benefit and will pursue avenues towards fulfillment other than work.

This new cultural consensus will thus pave the way to new (re)distributional policies, new ways for a society to share its wealth (more on that below).

Part of the same cultural shift we should ditch the Puritan work ethic ("There will be sleeping enough in the grave," as Benjamin Franklin liked to say) and instead rediscover the lost art of active rest : hiking, playing instruments, painting, chatting with friends in pubs. Unlike trancing out on Twitter or grazing Netflix endlessly, this kind of leisure is regenerative because it is woven of intentional activity, stimulating the mind and the spirit. And it makes those working more productive to boot.

Work is a central social value, and consequently the pivot of the system of distribution of wealth, benefits, and protection. As Daniel Susskind puts it,

Incorporated in the self-image of most Westerners is the Protestant Ethic that only hard work and doing things are really serious activities. Moreover, in industrial societies "work" is implicitly defined as paid, as done in an employer's time rather than in one's own "leisure" time, and at the employer's behest rather than for one's own purposes. Hence the confusion over whether housewifery is work, or whether self-directed and creative ways of earning one's bread (such as writing novels or throwing pots) are "real" work. Given these views, massive unemployment could be more soul-destroying than the most repetitive of factory jobs—even though people's "leisure" time for creative hobbies (sic) would be correspondingly increased. Although a shortening of the labor day may not reduce work in the same proportion (since it may become more intensive), certain types of unskilled and semiskilled work might be largely taken over by machines. Were the time currently spent on drudgery to be devoted to varied, creative, and autonomous work that is satisfying in itself (a state of affairs that presupposes corresponding changes in the social definition of work), unemployment would not result and people would be more fulfilled in their working lives. Otherwise, and to the extent that socially accepted ways of thinking about "work" did not change quickly enough, communities influenced by the Protestant Ethic would experience a deep social malaise. For if a man has been brought up to see himself as an industrious provider for his family and the community, enforced "leisure" may not only bore him (a boredom that could be partly alleviated by the home terminal), but may cause him destructively to define himself to himself as a social parasite. (Artificial Intelligence and Natural Man)A recent article echoes these words written 40 years ago, and draws our attention to boredom, the hidden risk of automation that no one is talking about, which leads (among other things) to significant health problems; the overall argument of the article is that "a less effortful, more efficient life may not be a better life." With a little more dramatic impact, one can say that maybe we should not "fear zombie AI [but instead] worry about humans who have nothing left to do in the universe except play awesome video games. And who know it."

It seems to me that is urgently needed a new cultural consensus, one that provides an answer to the thorny question "When technology can do nearly anything, what should I do, and why?" It would have to accommodate the fact that work will be a choice not a necessity, and that a considerable share of the population will live on some sort of means-independent social benefit and will pursue avenues towards fulfillment other than work.

This new cultural consensus will thus pave the way to new (re)distributional policies, new ways for a society to share its wealth (more on that below).

Part of the same cultural shift we should ditch the Puritan work ethic ("There will be sleeping enough in the grave," as Benjamin Franklin liked to say) and instead rediscover the lost art of active rest : hiking, playing instruments, painting, chatting with friends in pubs. Unlike trancing out on Twitter or grazing Netflix endlessly, this kind of leisure is regenerative because it is woven of intentional activity, stimulating the mind and the spirit. And it makes those working more productive to boot.

* * *

Work is a central social value, and consequently the pivot of the system of distribution of wealth, benefits, and protection. As Daniel Susskind puts it,

The relevant question is not "Will machines replace humans?", but "How will we distribute wealth in a world when there will be less - or even no - work?" Today, for most people, their job is their seat at the economic dinner table, and in a world with less work or even without work, it won't be clear how they get their slice.Darrell West suggests that, as new technology allows our society to be more productive with less people working, we should redefine the concept of work to include volunteering, parenting, and mentoring and that we expand leisure time. There are signs that we might be heading in this direction, like the calls to include unpaid and household work in GDP calculations. West further argues that by expanding the definition of work and encouraging the government to provide benefits, such as health care and retirement contributions, to citizens who are working in nontraditional ways, we can alleviate many of the growing pains associated with these technological advancements and avoid major political instability.

Most young people are not prepared for long-term unemployment and the associated social stigma. This has serious negative consequences on both personal and social levels. In the absence of job-providing solutions, we should help them build financial and psychological resilience and internalize checks against anti-social behavior.

The aforementioned article in The Guardian draws our attention to the fact that

* * *

The aforementioned article in The Guardian draws our attention to the fact that

The insecurity that automation brings will soon demand the comprehensive replacement of a benefits system that does almost nothing to encourage people to acquire new skills, and works on the premise that it can shove anyone jobless into exactly the kind of work that’s under threat. [...] In both schools and adult education, the system will somehow have to pull as many people as it can away from the most susceptible parts of the economy, and maximize the numbers skilled enough to work in its higher tiers.As illustrated by this quote, education and/or training are almost universally seen as the most efficient responses to AI and automation. Although used interchangeably, these have different requirements, outputs, and societal impact.

Training will assure that you can solve the problems that are already solved. But electronic computers can do that, much better than you. If you want a good job in the 21st century, you have to be able to solve problems that are not yet solved. If you want that skill, opt for education, not training. Find your own patterns, and make up your own stories. (Macroeconomic Patterns and Stories)

A report on the Future of Skills makes a similar point, by emphasizing that the future workforce will need broad-based knowledge in addition to the more specialized features needed for specific occupations; higher-order cognitive skills (originality, fluency of ideas and active learning) are also crucial.

The cultural consensus mentioned above would allow - or perhaps even force - us to rethink the social "rules of entitlement", to restructure and reorient the system of access to, and distribution of, cognitive resources and skills. This is needed because

The cultural consensus mentioned above would allow - or perhaps even force - us to rethink the social "rules of entitlement", to restructure and reorient the system of access to, and distribution of, cognitive resources and skills. This is needed because

Just as most advanced economies are reaching the point at which it becomes difficult to improve educational attainment any further, the level of education needed to participate in the most lucrative corners of the economy is growing beyond the reach of the vast majority of workers.Education and training programs should be tailored to the target group : for the less educated (and most in need), the idea of lifelong learning is repulsive while workplace learning might work much better. They might become highly skilled users / handlers of exoskeletons or work buddies and mentors for cobots and collaborative AI.

Equal access to education is widely acknowledged, but little consideration seem to be given to the language barrier - a particularly European issue. With little or no knowledge of English, those most in need have only access to limited, and perhaps obsolete, opportunities in the national language.

Last but not least, we might misunderestimate the required effort : "To enable new ways of working will require a skills revolution on a scale we’ve never before seen. Most attempts to foster lifelong learning or successful retraining have fallen short."

* * *

My other posts relevant to the topic